Search for seaweed: why it matters

Seaweeds can tell us a lot about our seas and climate change, so it’s vital that we keep track of what’s happening to them. That’s where citizen scientists come in, explains Professor Juliet Brodie, who leads the Big Seaweed Search

Professor Juliet Brodie

Professor Juliet Brodie

Seaweeds are the forests of the sea. They provide shelter and food for thousands of marine animals: seals swim through them, squids lay their eggs among them and young fish use seaweeds as a protective habitat. “Seaweeds are fundamental to all the organisms that live in the habitats they create; they provide a place of safety,” says Professor Juliet Brodie, a research scientist studying seaweeds at the Natural History Museum in London.

Seaweeds protect our coasts from storm and wave damage, store carbon and produce more oxygen than forests on land. Seaweeds are also indicators of climate change: as sea temperatures rise, we see changes in their distribution and for some, such as the large brown kelps, losses and declines in many parts of the world.

There are more than 650 seaweed species in the UK, each with their own unique characteristics – some wavy and wrinkled, others with frilly or narrow strap-like fronds. They are beautiful in their own right, but less easy to observe (such as on remote seashores or under the water) and more difficult to identify than colourful flowers, butterflies or birds, and so fewer people document observations.

That was one of the reasons why Juliet had the idea to set up the Big Seaweed Search. “I was watching the RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch in 2006, and I suddenly thought: ‘Why don’t we do something like that for seaweed?’ It took us longer than expected to get a project off the ground because we had to think about the species to include, the methods to use, and we had to make sure we had sound science behind it,” she says.

“I’d been hearing anecdotally that large species of brown seaweeds were beginning to disappear, but the data wasn’t very clear at that point, so we needed a more substantial data set. This is where the citizen scientists come in.”

The Big Seaweed Search, now a partnership between The Natural History Museum and the Marine Conservation Society, has become a vital project to monitor certain species of seaweed and over time to identify changes in our ocean.

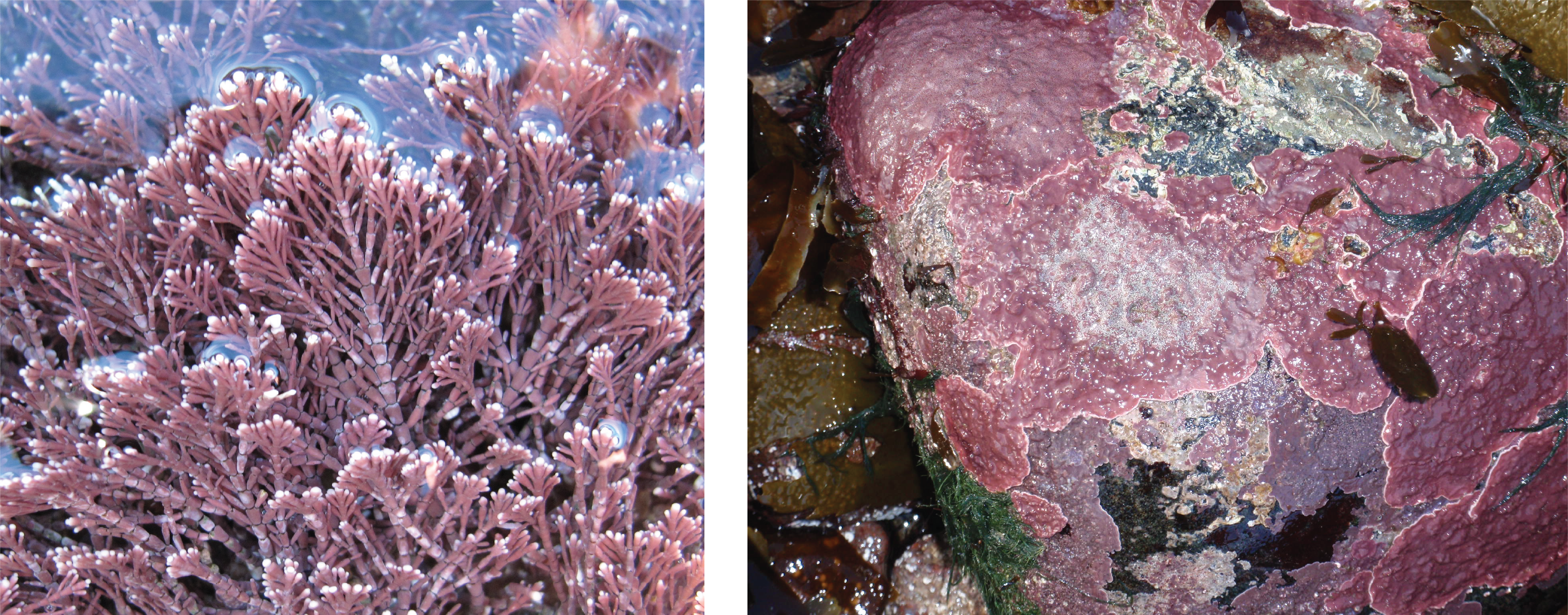

Seaweeds can be affected by ocean acidification where the sea absorbs increasing amounts of carbon dioxide. Species such as Coral weed and Calcified crust may have their chalky skeletons compromised in these conditions, so there will be changes in the abundance and distribution of these species.

Coral weed (left), Calcified crust (right)

Coral weed (left), Calcified crust (right)

Seaweeds can be affected by ocean acidification where the sea absorbs increasing amounts of carbon dioxide. Species such as Coral weed and Calcified crust may have their chalky skeletons compromised in these conditions, so there will be changes in the abundance and distribution of these species.

Coral weed

Coral weed

Calcified crust

Calcified crust

The presence or absence of certain seaweeds such as Dabberlocks, Serrated wrack, Bladder wrack and Knotted wrack can help to indicate the impact of increasing sea temperature.

Dabberlocks (left), Serrated wrack (right)

Dabberlocks (left), Serrated wrack (right)

Bladder wrack (left), Knotted wrack (right)

Bladder wrack (left), Knotted wrack (right)

The presence or absence of certain seaweeds such as Dabberlocks, Serrated wrack, Bladder wrack and Knotted wrack can help to indicate the impact of increasing sea temperature.

Dabberlocks

Dabberlocks

Serrated wrack

Serrated wrack

Bladder wrack

Bladder wrack

Knotted wrack

Knotted wrack

It’s also important to track the spread of non-native species such as Wakame and Wireweed, which can potentially outcompete indigenous seaweed species for food, light or space. “Wakame is a big seaweed and it’s potentially one of the most problematic,” says Juliet.

Wakame (left), Wireweed (right)

Wakame (left), Wireweed (right)

It’s also important to track the spread of non-native species such as Wakame and Wireweed, which can potentially outcompete indigenous seaweed species for food, light or space. “Wakame is a big seaweed and it’s potentially one of the most problematic,” says Juliet.

Wakame

Wakame

Wireweed

Wireweed

Making a difference

Juliet values the input from citizen scientists, who have already contributed a wealth of data about seaweeds around the UK. “I see citizen science tying up with the research we do and the resources we have. It’s a way for us all to exchange knowledge and I would like to get more people involved, and for them to feel like they’re making a difference to their local areas.”

The data gathered from previous years of the Big Seaweed Search has been used in research published by Juliet, enabling the distribution of large brown seaweeds of the British Isles to be mapped, providing a baseline from which to study change.

“We made some predictions in a paper a few years ago, and these predictions are coming true, but much quicker...

Gain full access to