Search for seaweed: why it matters

Seaweeds can tell us a lot about our seas and climate change, so it’s vital that we keep track of what’s happening to them. That’s where citizen scientists come in, explains Professor Juliet Brodie, who leads the Big Seaweed Search

Professor Juliet Brodie

Professor Juliet Brodie

Seaweeds are the forests of the sea. They provide shelter and food for thousands of marine animals: seals swim through them, squids lay their eggs among them and young fish use seaweeds as a protective habitat. “Seaweeds are fundamental to all the organisms that live in the habitats they create; they provide a place of safety,” says Professor Juliet Brodie, a research scientist studying seaweeds at the Natural History Museum in London.

Seaweeds protect our coasts from storm and wave damage, store carbon and produce more oxygen than forests on land. Seaweeds are also indicators of climate change: as sea temperatures rise, we see changes in their distribution and for some, such as the large brown kelps, losses and declines in many parts of the world.

There are more than 650 seaweed species in the UK, each with their own unique characteristics – some wavy and wrinkled, others with frilly or narrow strap-like fronds. They are beautiful in their own right, but less easy to observe (such as on remote seashores or under the water) and more difficult to identify than colourful flowers, butterflies or birds, and so fewer people document observations.

That was one of the reasons why Juliet had the idea to set up the Big Seaweed Search. “I was watching the RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch in 2006, and I suddenly thought: ‘Why don’t we do something like that for seaweed?’ It took us longer than expected to get a project off the ground because we had to think about the species to include, the methods to use, and we had to make sure we had sound science behind it,” she says.

“I’d been hearing anecdotally that large species of brown seaweeds were beginning to disappear, but the data wasn’t very clear at that point, so we needed a more substantial data set. This is where the citizen scientists come in.”

The Big Seaweed Search, now a partnership between The Natural History Museum and the Marine Conservation Society, has become a vital project to monitor certain species of seaweed and over time to identify changes in our ocean.

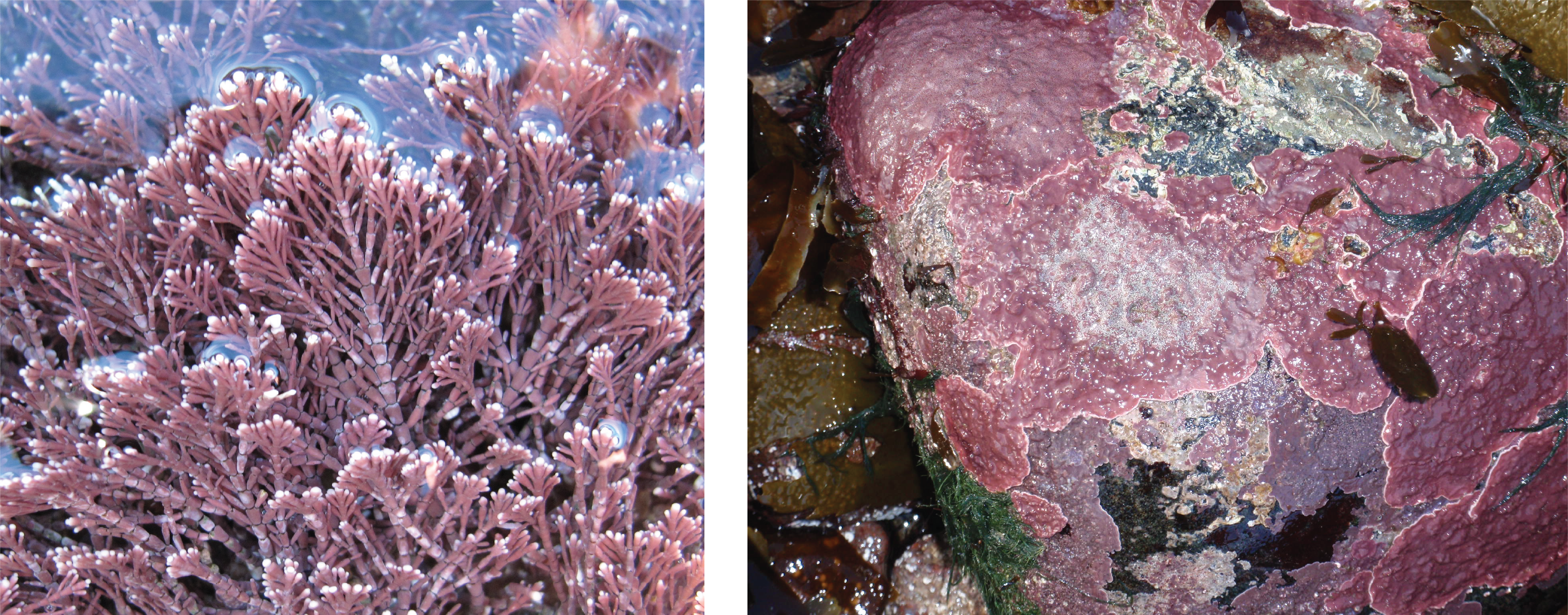

Seaweeds can be affected by ocean acidification where the sea absorbs increasing amounts of carbon dioxide. Species such as Coral weed and Calcified crust may have their chalky skeletons compromised in these conditions, so there will be changes in the abundance and distribution of these species.

Coral weed (left), Calcified crust (right)

Coral weed (left), Calcified crust (right)

Seaweeds can be affected by ocean acidification where the sea absorbs increasing amounts of carbon dioxide. Species such as Coral weed and Calcified crust may have their chalky skeletons compromised in these conditions, so there will be changes in the abundance and distribution of these species.

Coral weed

Coral weed

Calcified crust

Calcified crust

The presence or absence of certain seaweeds such as Dabberlocks, Serrated wrack, Bladder wrack and Knotted wrack can help to indicate the impact of increasing sea temperature.

Dabberlocks (left), Serrated wrack (right)

Dabberlocks (left), Serrated wrack (right)

Bladder wrack (left), Knotted wrack (right)

Bladder wrack (left), Knotted wrack (right)

The presence or absence of certain seaweeds such as Dabberlocks, Serrated wrack, Bladder wrack and Knotted wrack can help to indicate the impact of increasing sea temperature.

Dabberlocks

Dabberlocks

Serrated wrack

Serrated wrack

Bladder wrack

Bladder wrack

Knotted wrack

Knotted wrack

It’s also important to track the spread of non-native species such as Wakame and Wireweed, which can potentially outcompete indigenous seaweed species for food, light or space. “Wakame is a big seaweed and it’s potentially one of the most problematic,” says Juliet.

Wakame (left), Wireweed (right)

Wakame (left), Wireweed (right)

It’s also important to track the spread of non-native species such as Wakame and Wireweed, which can potentially outcompete indigenous seaweed species for food, light or space. “Wakame is a big seaweed and it’s potentially one of the most problematic,” says Juliet.

Wakame

Wakame

Wireweed

Wireweed

Making a difference

Juliet values the input from citizen scientists, who have already contributed a wealth of data about seaweeds around the UK. “I see citizen science tying up with the research we do and the resources we have. It’s a way for us all to exchange knowledge and I would like to get more people involved, and for them to feel like they’re making a difference to their local areas.”

The data gathered from previous years of the Big Seaweed Search has been used in research published by Juliet, enabling the distribution of large brown seaweeds of the British Isles to be mapped, providing a baseline from which to study change.

“We made some predictions in a paper a few years ago, and these predictions are coming true, but much quicker than we expected,” she says. “I’m eternally grateful to all the people who have sent in their results of the Big Seaweed Search, and I hope they know how valuable the data is that they collect.”

A community of searchers

Juliet also sees the benefit of the communal element of the Big Seaweed Search. “You can start wanting to change the world and knowing that you can’t do it on your own, but joining something like this, you meet lots of like-minded people who want to make a difference. By using our science, skills and experience, we can build these strong teams.”

While the activity is hugely beneficial to seaweed studies, “it’s also fun to do, like a sort of treasure hunt,” says Juliet. “Volunteers often tell us how much they enjoy taking part. A local branch of the charity Mind got in touch in the early days of the project as they saw the value in the activity of getting people outside, moving around, focusing on the survey and involved in their local coastal areas.”

Seaweed isn’t just for spotting, “there’re so many amazing potential uses,” says Juliet. “One of the Big Seaweed Search ideas we would like to try is to get volunteers to take seaweed samples (which have been cleaned) into homes with people such as those with dementia so they can see the colours and shapes, feel the textures and enjoy the different sensory experiences.”

Juliet has worked with many different people around the world involved in seaweed, including, more recently, in the seaweed farming industry. “I’ve started to think more about the human angle. These seaweed farms are quite remote and they’re very important for the local families. It’s their income and their livelihoods, but it’s getting more difficult to grow the seaweeds in some parts of the world with climate change, so we’re trying to find solutions to that.”

A passion for seaweed

Juliet’s interest in seaweed started in her twenties. “I was working in West Wales and because I was able to scuba dive, I was asked if I would like to undertake some survey work in relation to setting up Marine Nature Reserves as part of the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act. Two members of the team in particular, who I still work with now 40 years later, showed me what seaweeds to look for and how to recognise and record them, which was a great start,” she says.

“I then went on to do my PhD in Ireland and did a lot of laboratory-based work with seaweeds. I started by just being curious: what’s that seaweed? Why is it there? What does it do? How does it reproduce? And as I started to travel to different parts of the world doing more fieldwork, I realised there were so many questions I could address using seaweed.”

Juliet encourages Marine Conservation Society members to join the Big Seaweed Search Week from 29th July to 6th August. “It’s a great way to contribute to our work, but it doesn’t have to stop there. You can join us as volunteers, making observations regularly in your local areas, which is even more helpful to see the change in specific areas,” she says.

A passion for seaweed

Juliet’s interest in seaweed started in her twenties. “I was working in West Wales and because I was able to scuba dive, I was asked if I would like to undertake some survey work in relation to setting up Marine Nature Reserves as part of the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act. Two members of the team in particular, who I still work with now 40 years later, showed me what seaweeds to look for and how to recognise and record them, which was a great start,” she says.

“I then went on to do my PhD in Ireland and did a lot of laboratory-based work with seaweeds. I started by just being curious: what’s that seaweed? Why is it there? What does it do? How does it reproduce? And as I started to travel to different parts of the world doing more fieldwork, I realised there were so many questions I could address using seaweed.”

Juliet encourages Marine Conservation Society members to join the Big Seaweed Search Week from 29th July to 6th August. “It’s a great way to contribute to our work, but it doesn’t have to stop there. You can join us as volunteers, making observations regularly in your local areas, which is even more helpful to see the change in specific areas,” she says.

Top tips for taking part in the Big Seaweed Search

You can find guides and a recording form on our website. Here are Juliet’s expert tips for searching and reporting your finds:

Rocky shores are the best place to spot seaweed – but don’t go alone and always be mindful of the tides and weather.

Submit pictures – they’re essential to validate the data so that the results can be used in future studies.

Make sure the seaweed you record is still attached, and therefore alive, to be validated in the research.

Follow the process in the Big Seaweed Search guides – the collection methods must be comparable for good quality data.

The easiest seaweeds to identify on the guide are the three big browns: the Serrated wrack, the Bladder wrack and the Knotted wrack.

Make sure you submit the data: it’s invaluable for us. A lot of people get involved in the Big Seaweed Search, but we often find they don’t submit their data, as they forget or run out of time.

If you enjoy the project, set up regular seaweed searches at your local beach.

Meet a seaweed searcher

Thongweed and Wireweed

Thongweed and Wireweed

Volunteer Chris Townsend runs Big Seaweed Search surveys with a group of local volunteers on the rocky shore at Porthcurnick Beach, next to Portscatho, Cornwall. “We contribute to real scientific research through this great citizen science project. I’d studied marine botany decades ago, and love seaweeds. The Big Seaweed Search has helped me stay involved in both science and community life,” says Chris. It has also inspired her to run seaweed workshops, raising awareness about seaweeds and climate change.

Chris has spotted quite a few species listed in the Big Seaweed Search guide. “Thongweed and Serrated wrack are brown seaweeds, which love cold water. They are found on the low shore – and can be seen best at a very low tide. They may be affected by warmer sea water caused by climate change,” she says. She’s also identified Wireweed, which is a non-native seaweed, and Coral weed, a red seaweed with a chalky skeleton.

“My tip for identifying seaweeds is to check their position on the shore. So, for example, Channelled wrack only ever occurs on the upper shore,” she says.

Volunteer Chris Townsend runs Big Seaweed Search surveys with a group of local volunteers on the rocky shore at Porthcurnick Beach, next to Portscatho, Cornwall. “We contribute to real scientific research through this great citizen science project. I’d studied marine botany decades ago, and love seaweeds. The Big Seaweed Search has helped me stay involved in both science and community life,” says Chris. It has also inspired her to run seaweed workshops, raising awareness about seaweeds and climate change.

Chris has spotted quite a few species listed in the Big Seaweed Search guide. “Thongweed and Serrated wrack are brown seaweeds, which love cold water. They are found on the low shore – and can be seen best at a very low tide. They may be affected by warmer sea water caused by climate change,” she says. She’s also identified Wireweed, which is a non-native seaweed, and Coral weed, a red seaweed with a chalky skeleton.

Thongweed and Wireweed

Thongweed and Wireweed

“My tip for identifying seaweeds is to check their position on the shore. So, for example, Channelled wrack only ever occurs on the upper shore,” she says.

Your Ocean stories

We’re fighting for a cleaner, better-protected, healthier ocean: one we can all enjoy. Thank you for your support.

Credits

Video: Brent Durand/Moment Video RF/Getty Images. Photos: NHM; Mike Guiry; Keith Hiscock; Jack Sewell; Lucie Goodayle/NHM London; Chris Townsend; Juliet Brodie. Illustration: Willa Gebbie