Restoring

a lost world

Oyster reefs encourage a profusion of marine life, from feather stars to crabs – and now have been shown to double biodiversity in a decade. Joe Shute explores the incredible potential of our project to reintroduce native oysters in the Dornoch Firth

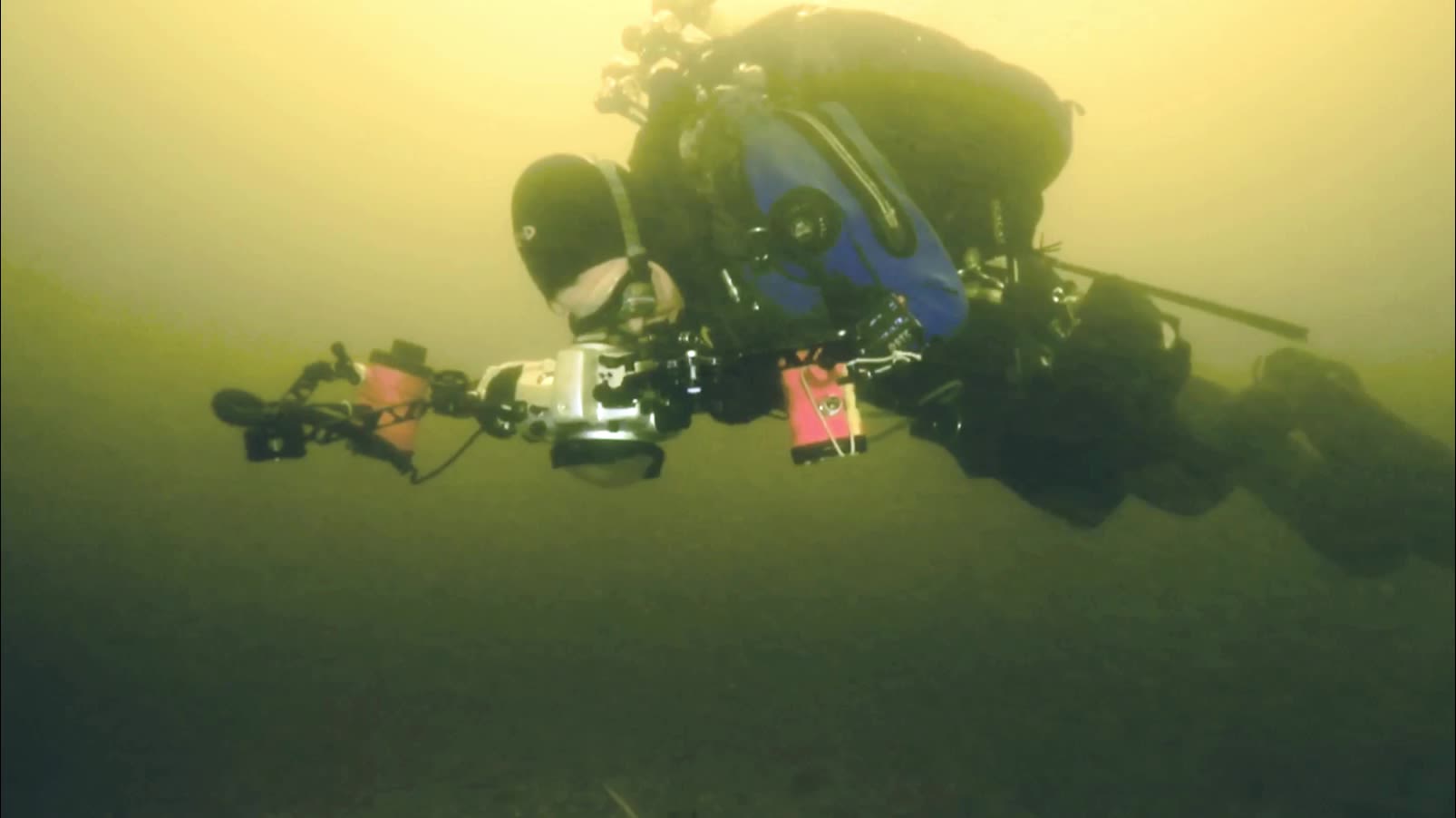

To dive down upon a native European oyster reef is to visit a lost Atlantis. Fronds of brightly coloured seaweed wave in the clear water filtered by the bivalve molluscs. Within the crevices of the layered oyster shells, teems an abundance of life.

Feather stars (which are from the crinoid family of marine invertebrates) perch on top of oyster shells to more efficiently catch morsels of food by holding their frilly arms higher into the water. Sea toads, a type of crab, lurk in the shadows, camouflaged by a spiky shell-like carapace, which can reach up to 60mm in length. Darting across the reefs are blenny and goby fish, dabs and dragonets, the eel-like butterfish and pipe fish, which possess magnificent seahorse snouts.

Goby fish

Goby fish

Thriving biodiversity in Loch Ryan

Thriving biodiversity in Loch Ryan

Dab

Dab

Native oyster

Native oyster

Common feather star

Common feather star

Dragonet

Dragonet

Oysters have long been regarded as ecosystem engineers, but scientists at Edinburgh’s Heriot-Watt University recently demonstrated that restored reefs could lead to a doubling of biodiversity in just 10 years. Naomi Kennon, a restoration ecologist and researcher at the university who was lead author on the paper, published in March in the scientific journal PLOS ONE, describes the oyster beds as “analogous to a forest” due to the astonishing variety of life which thrives there.

As explained by Bill Sanderson, Professor of Marine Biodiversity at Heriot-Watt University, who was involved in the research, native oyster beds simply mean an “enhancement of life” and “an awful lot more of everything”.

A pioneering partnership

The research is part of the pioneering Dornoch Environmental Enhancement Project (DEEP), a partnership between the Marine Conservation Society, Heriot-Watt University and The Glenmorangie Company, who are working to restore a long-lost oyster reef in the Dornoch Firth in north-east Scotland. Despite their ecological importance, native oyster reefs remain vanishingly rare around the UK having been fished almost to extinction over the course of the 19th century. It is hoped DEEP can inspire similar efforts across the country, and beyond.

First conceived of around 10 years ago, to date the project has already returned 76,800 oysters to the Dornoch Firth seabed and is aiming to reintroduce four million across the 20km-long estuary by 2030. The Heriot-Watt University scientists researched the biodiversity of the native oyster fishery at Loch Ryan in south-west Scotland, which has allowed the team to predict what the Dornoch Firth reef could look like once oysters are fully restored.

As well as dramatically enhancing marine biodiversity, the oysters will help lock up carbon across the estuary. “If we want to address the nature and climate emergencies we need to have everybody working together for solutions,” explains Calum Duncan, Head of Conservation Scotland, at the Marine Conservation Society. “The more beacons we have and examples of what that can look like in practice, the better to inspire other projects.”

The Glenmorangie Company Distillery in Tain was established on the banks of the Dornoch Firth in 1843. The oysters will supplement an anaerobic digestion facility installed by the distillery in 2017, which already purifies up to 95 per cent of the waste water it releases into the firth. The shared vision, explains Calum, is that the oysters will help purify the remaining five per cent of the waste water. After all, it has been estimated that a single native European oyster can filter up to 200 litres of water a day.

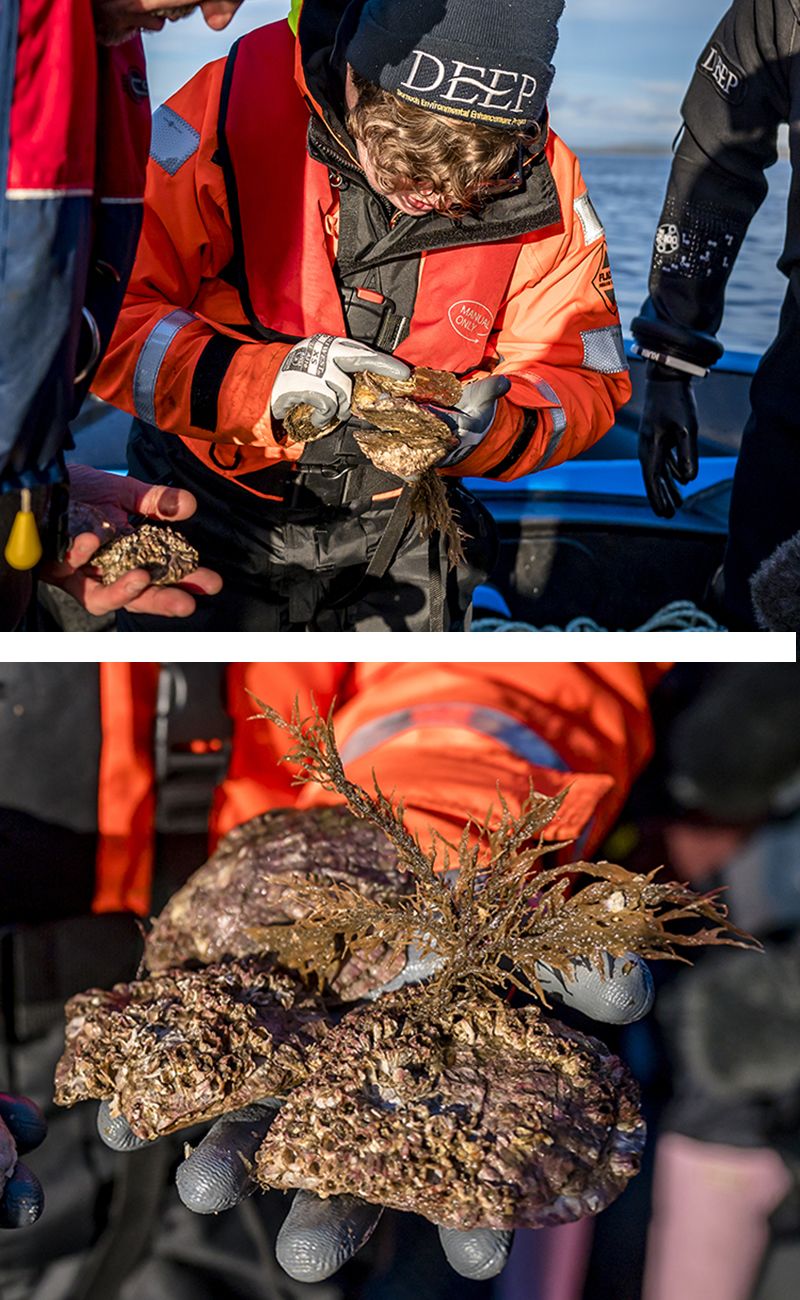

Marine Conservation Society’s Calum Duncan and the DEEP team restoring native oysters to the Dornoch Firth

The DEEP team restore oysters to the Dornoch Firth

Oysters were the street food of the poor in Victorian times, as shown in this mid-19th century cartoon

Oysters were the street food of the poor

First becoming established around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age, native European oyster beds once stretched from Norway to the Mediterranean and were prevalent across the British coast (including the Dornoch Firth). They have been eaten as food since at least Roman times, but the Industrial Revolution spelled disaster for the oysters as newly expanded rail networks connected remote coastal locations with rapidly expanding urban populations. Now associated with fine dining, back then the seafood was a staple of the working poor, shucked on street corners for a nutritious snack. Their rapid destruction, Professor Bill Sanderson explains, was “one of the first fish stocks that we ever fished to extinction in lots of places throughout Europe”.

Oysters have a complex life cycle, which is still being fully unpicked by scientists. Typically, they will change their sex once a year until reaching reproductive age at around five years old. Oysters mate by the males releasing sperm into the water, which is drawn in by the females as they filter feed, who then fertilise eggs stored inside their shell. After a week or so, the larvae hatch and feed on plankton before settling to the bed. To effectively mate, oysters need to reside close by one another and, crucially, be left undisturbed.

Overfishing, therefore, has spelled disaster for the species. Native oyster populations in the UK have declined by around 95 per cent since the mid 19th century. Globally, around 85 per cent of oyster reefs have been lost over the past two centuries and they are now considered one of the most threatened marine habitats in Europe and the world.

Today the vast bulk of oysters on sale in the UK are Pacific oysters. Loch Ryan remains the last native oyster commercial fishery in Scotland and it operates a six-year rotational harvest policy, which allows the reefs sufficient time to recover between being dredged. The Loch Ryan oysters are being used to help restore the Dornoch Firth reefs, alongside two other suppliers situated elsewhere in Scotland.

The study in Loch Ryan looked at the change in biodiversity over six years…

Year 1

Year 6

…As oyster populations grow, the biodiversity of the reef increases too

The study in Loch Ryan looked at the change in biodiversity over six years…

Year 1

Year 6

…As oyster populations grow, the biodiversity of the reef increases too

Leading a revival

There is little art to actually reintroducing the oysters: ‘random broadcast distribution’ is the official term, which translates to simply heading out in a boat and chucking them off the side. However there has been significant work behind the scenes to optimise the process of restoration, including survival trials monitoring a few hundred of the oysters, which particularly thrive in subtidal coastal waters.

Ensuring the close involvement of the local community has also been key to the project. Tom Bannerman, who is the Marine Conservation Society’s Dornoch Restoration Officer, has worked with 14 local schools on the project as well as local Beaver, Scouts and Cubs groups, running workshops, beach cleans and seaweed searches (to help analyse marine life). He has also engaged in the region of 20,000 visitors to the Glenmorangie Distillery itself and undertaken a wide-ranging community survey. In time it is hoped local people will be involved in helping deploy the oysters themselves.

Tom, 24, who studied marine biology at university and has a Master’s degree in environmental science and conservation, grew up just 10 miles from the shores of the Dornoch Firth and is well aware of its local importance (alongside its international significance for marine, coastal and bird life). “The Dornoch Firth holds quite a special place in people’s hearts,” he says. “When a lot of people think about marine restoration projects they probably think of coral reefs and sandy beaches out on the Maldives. The fact they can have it just a few miles away is quite amazing.”

Heriot-Watt University’s Naomi Kennon examines oyster growth in the Dornoch Firth

Examining oyster growth in the Dornoch Firth

A lasting legacy

The DEEP project, Sanderson stresses, is not about restoring oyster fishing in the Dornoch Firth. The oysters that are returned there will remain in situ and be left undisturbed throughout a life cycle, which typically spans up to 20 years in the wild. The largest oyster Bill has ever encountered was the shell of a whopper retrieved from the seabed in the Shetland Isles, which measured 201mm and weighed nearly 1kg when landed. “That was an absolute monster,” he recalls. “We are talking about things that are very unfamiliar to us.”

But the hope is that the Dornoch Firth project can inspire even larger-scale restoration of native reefs elsewhere. The Moray Firth, for example, which Bill says could one day be replenished with Dornoch oysters.

Calum holds a similar long-term hope for the DEEP project. “The vision is you help unlock new opportunities for native oyster restoration or, in the right place, sustainable aquaculture,” he says. For now though, their efforts remain focused on restoring a lost world – one oyster shell at a time.

Your Ocean stories

We’re fighting for a cleaner, better-protected, healthier ocean: one we can all enjoy. Thank you for your support.

Credits

Video clip showing biodiversity in Loch Ryan from DEEP: Could biodiversity double in a decade?, courtesy of The Glenmorangie Company. Infographic demonstrating the change in biodiversity over six years: Based on illustration by SGW Illustrations in Kennon et al. (2023). Photos: Richard Shucksmith; Charné Hawkes Photography; MCS/Mark Kirkland; Paul Naylor; Cathy Lewis; Duncan1890/Digital Vision Vectors/Getty Images